Conceptual Aesthetics Without Political Grounding: bell hooks and the Limits of Making Moves: A Collection of Feminisms

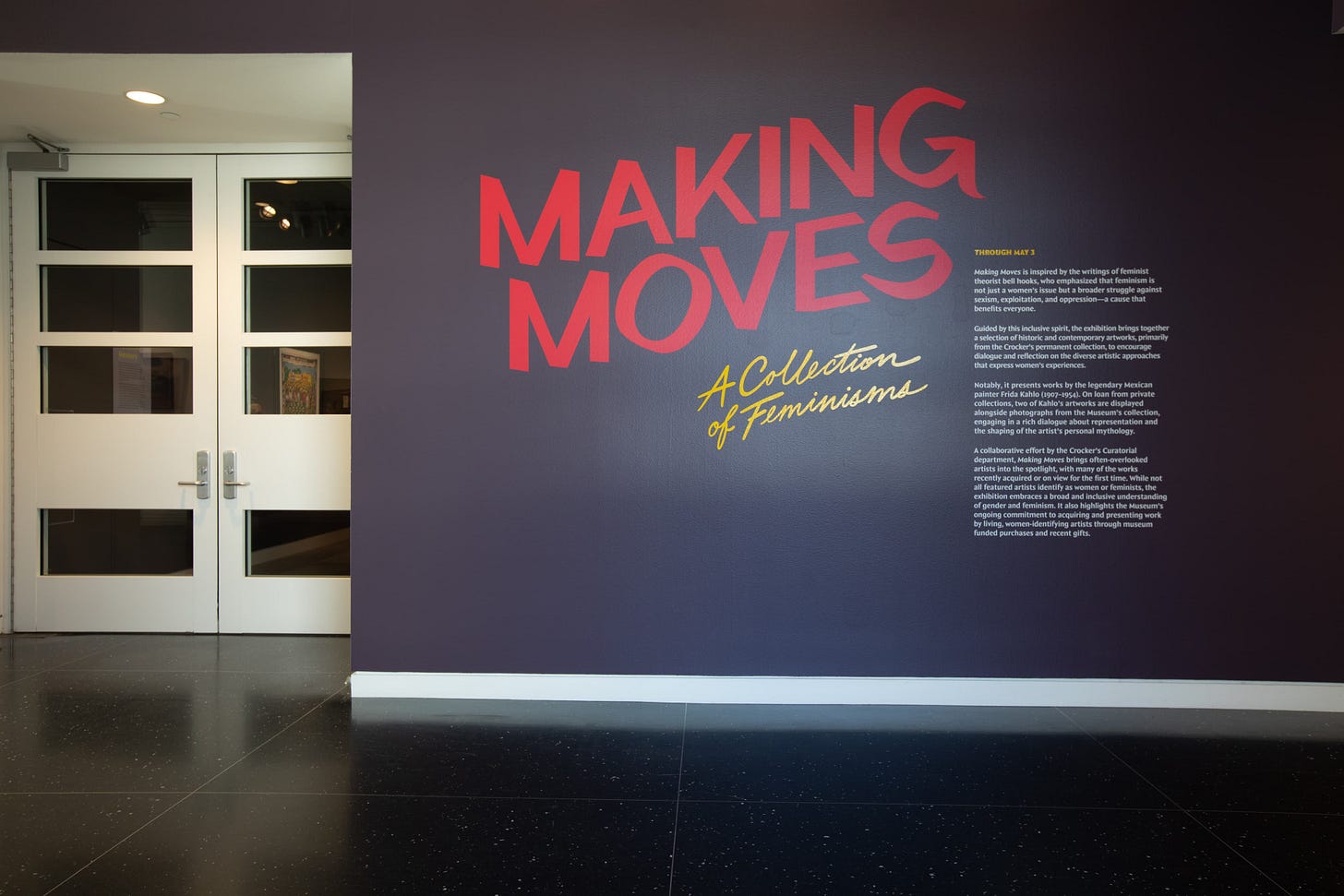

Crocker Art Museum’s latest exhibition, Making Moves: A Collection of Feminisms, positions itself as a feminist exhibition “inspired by the writings of bell hooks”, organizing over seventy works from the museum’s permanent collection around themes of self-representation, care, sentimentality, the erotic, and memory. Yet while hooks’ name anchors the exhibition’s conceptual framing, her writing is notably absent from its interpretive materials. This omission is not incidental. It reveals a broader curatorial tension between feminism as a political framework and feminism as a thematic or aesthetic category.

bell hooks (1952–2021) was a Black feminist theorist, cultural critic, writer, and educator whose work fundamentally reshaped feminist thought by insisting that race, class, gender, and power be understood as inseparable systems. Writing across theory, memoir, pedagogy, art criticism, and children’s literature, hooks insisted that feminism be both politically rigorous and radically accessible. Throughout her career, hooks challenged institutions—universities, media, museums, and cultural canons—to confront how domination operates through representation, education, love, and memory. Her writing emphasized that theory must be lived, named plainly, and made available to everyone.

hooks consistently defined feminism as “a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression.” This formulation demands structural analysis—of race, class, gender, and power—rather than broad gestures toward inclusion or representation. In Making Moves, however, hooks’ framework is paraphrased rather than cited, translated into institutional language that emphasizes “women’s experiences” and diversity of expression. The result is a softened feminism, one that privileges affect and visibility over critique and accountability.

The press release proclaims that Making Moves “makes space for open-ended feminist thought,” yet offers no definition of feminism, no engagement with feminist theory, and no didactic materials situating bell hooks’ political framework. bell hooks repeatedly warned that feminism loses its transformative potential when it is rendered vague or purely thematic. In Feminism Is for Everybody, she defines feminism as “a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression,” a clarity absent from the exhibition’s interpretive approach. By substituting thematic openness for political grounding, the exhibition frames feminism as an aesthetic sensibility rather than a critical methodology, placing the burden of interpretation on the viewer while absolving the institution of pedagogical responsibility.

The exhibition’s treatment of self-representation exemplifies this slippage. As bell hooks argues in Black Looks and Art on My Mind, representation is a site of political struggle shaped by histories of domination and the gaze. Without this grounding, self-representation in Making Moves risks functioning as an expressive category rather than a refusal of imposed narratives. Similarly, the theme of care gestures toward relationality and tenderness, yet remains detached from hooks’ insistence that care and love function as ethical practices tied to justice, labor, and resistance, most clearly developed in All About Love and Teaching Community.

Sentimentality and memory are likewise framed as affective registers rather than contested terrains. hooks repeatedly cautions against sentiment when it obscures power, insisting instead that memory functions as counter-history—embodied, racialized, and tethered to place. In foregrounding feeling without historical or structural analysis, Making Moves neutralizes the radical potential of these themes. The erotic, too, is treated primarily as visual expression, bypassing hooks’ insistence that desire is shaped by patriarchy, trauma, and domination, and therefore is not inherently liberatory.

A November 2, 2025 blog post, further notes that the exhibition “embraces an inclusive view of gender and feminism, resisting definitions and boundaries in favor of diverse perspectives and lived experiences.”

Yet this resistance to definition directly contradicts hooks’ repeated insistence that feminism requires clarity to remain politically effective

As hooks writes in Feminism is for Everybody:

“Feminist politics is losing momentum because feminist movement has lost clear definitions. We have lost those definitions. Let’s reclaim them. Let’s share them. Let’s start over. Let’s have T-shirts and bumper stickers and postcards and hip-hop music, television and radio commercials, ads everywhere and billboards, and all manner of printed material that tells the world about feminism. We can share the simple yet powerful message that feminism is a movement to end sexist oppression. Let’s start there. Let the movement begin again.”1

By naming hooks while withholding her language, Making Moves transforms a rigorous Black feminist methodology into a curatorial mood. This move mirrors a broader institutional tendency to cite radical thinkers as inspiration while avoiding the political clarity they demand. hooks wrote accessibly and insistently so her work could circulate beyond the academy—not to be aestheticized, but to be used.

Ultimately, Making Moves offers feminism as a collection of gestures rather than a practice of critique. In doing so, it reveals the limits of conceptual alignment without intellectual commitment, reminding us that bell hooks does not provide themes for visual exploration so much as a framework for interrogating power—one the exhibition gestures toward, but ultimately refuses to inhabit.

There were numerous ways the exhibition could have meaningfully engaged bell hooks’ work while remaining accessible and visually compelling. By defining feminism clearly, citing hooks directly, and situating thematic concerns within her political framework, the curators could have invited viewers into feminism as a lived and contested practice rather than an open-ended aesthetic. hooks did not write to be inspirational in the abstract; she wrote to be used. Engaging her work fully would not have narrowed interpretation but expanded it, offering viewers the tools to understand feminism not only as something to feel, but as something to practice.

—

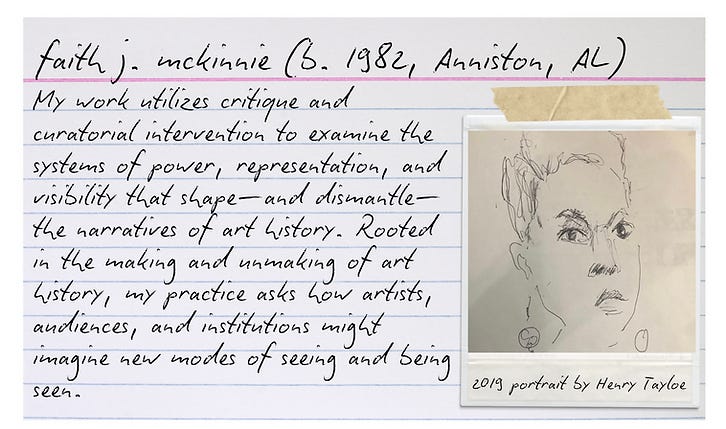

as a Black feminist critic + curator, and scholar of bell hooks, I offer this institutional critique with the hope that the Museum will deepen its engagement through programming and interpretative materials that meaningfully reflect hooks’ feminist politics.

bell hooks, Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2000),